Securitization without Security:

How Migration is Shaping the Global Order

notes from the field entry #7

The ones left behind

Author: Sarah Neubecker

Location: Miramar, Panama

Date: August 1, 2025

Miramar, Panama is a small cluster of houses and a few local businesses along the side of a dirt road, full of potholes, that cuts down Panama’s Caribbean coast. Tatiana and I bumped along that road late one night after a key informant assured us that we would see migrants leaving on small lanchas (boats) bound for southern Panama and then Colombia. It was unplanned and very last-minute, but after chasing leads and being left with questions about the “missing” migrants in Paso Canoas (see Entry #5), we were more than willing to seek answers in Miramar.

We woke up early the next morning to thunderstorms and wondered if the ocean was safe enough for migrants to travel. We headed down to the town’s dock, a small concrete slab with tethered lanchas around it. We passed by a Red Cross office advertising services specifically for migrants such as free wi-fi, charging ports, and international calling. We noticed several men sleeping on mattresses or sleeping pads outside, under awnings or porches. When the sun started to rise, the town awakened. The migrant men began to clean their sleeping areas and prepare for a day filled with waiting.

After some conversations and observations, we quickly learned that there were two groups of migrants in Miramar. One group was transitory; they had paid their $230 for a package that would take them all the way to Colombia and only stayed one night in town before taking the first available morning boat. The other group consisted largely of single men and some families who could not afford the lancha package. Some of them had been waiting for weeks, even months, for government buses to take them on a “humanitarian” boat to southern Panama. The government option was infrequent and unpredictable, but it was free.

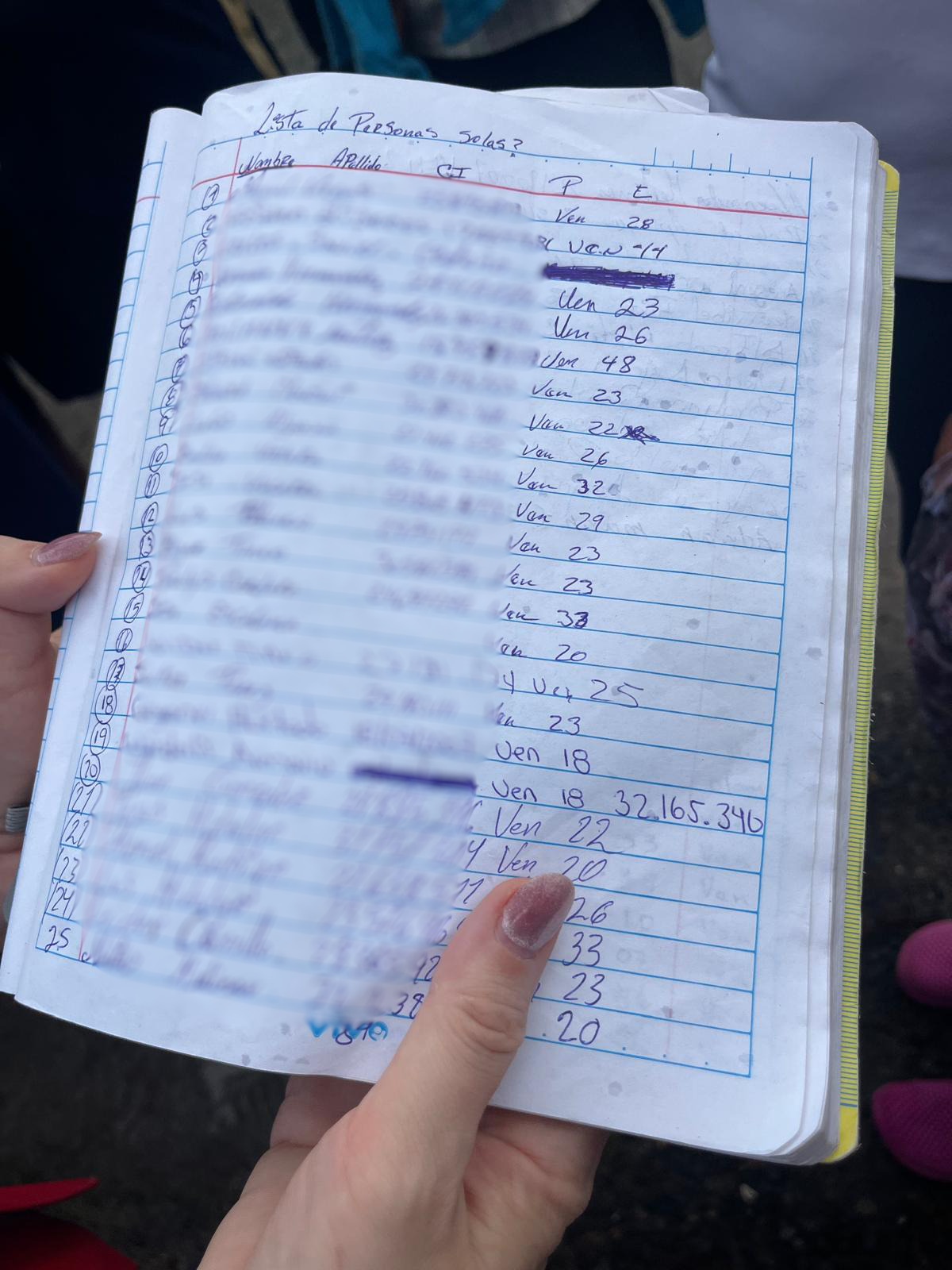

The day we conducted our observations, two government buses arrived, accompanied by dozens of Migration officials, military personnel, and some humanitarian organizations. One woman, who looked to be the migration officer in charge, waited as all the migrants in town ran to the road with their belongings in tow before reading off a list of names. These names were those who would get a seat on the next humanitarian lancha and would leave on the buses that day. The woman read about 20 names off the list–all of them women and children or men who were part of family units. Overlooked yet again, the forty single men we had seen milling about town became angry and frustrated, producing a list of their names, dates of birth, and identification numbers.

Despite being stuck with no money and nowhere to go, the government workers refused to take them, stating repeatedly that the priority is families with children. The buses departed, half empty, and the forty men trudged back to their sleeping quarters dispersed throughout the town, some going to shower in the ocean.

About an hour after the buses left, we witnessed the private lancha gearing up for departure. The second group of migrants, who had paid for a package and only recently arrived in Miramar, began to gather near the dock with their belongings. This group was identifiable by the yellow wristbands they wore. Each migrant was given a small plastic bag with a water bottle, a juice, and a bag of chips for the 6-7 hour boat ride. The lancha could barely fit the 25 people who would be leaving that morning and their luggage. By the time we watched the boat pull away, it was parallel to the water line and loaded to the brim. I noticed that young children wore ill-fitting adult lifejackets. No one from the government was present for the launch.

Some of the townspeople and “stuck” migrants came to see the lancha off. Among the passengers, there was an air of excitement and joy to be heading to Colombia and completing this part of the reverse migration journey–funny photos were taken and smiles were in no short supply. When the lancha left, the town went back to its normal rhythms, and the migrants who were left behind went back to waiting.

What we learned is that the border is not a chokepoint for migrants, but Miramar, a coastal town in central Panama, is. Migrants are waiting for a chance to get on a humanitarian boat or find an opportunity to earn money for the private lancha. In this small town, though, work is hard to come by and the likelihood of making enough cash for the package is slim. We also discovered why we were seeing so many families in places like Capurgana and Necoclí but not in Panama–the single men were getting stuck there.