Securitization without Security:

How Migration is Shaping the Global Order

notes from the field entry #5

Where Are All the Migrants?

Author: Tatiana Padilla

Location: Paso Canoas, Costa Rica

Date: July 18, 2025

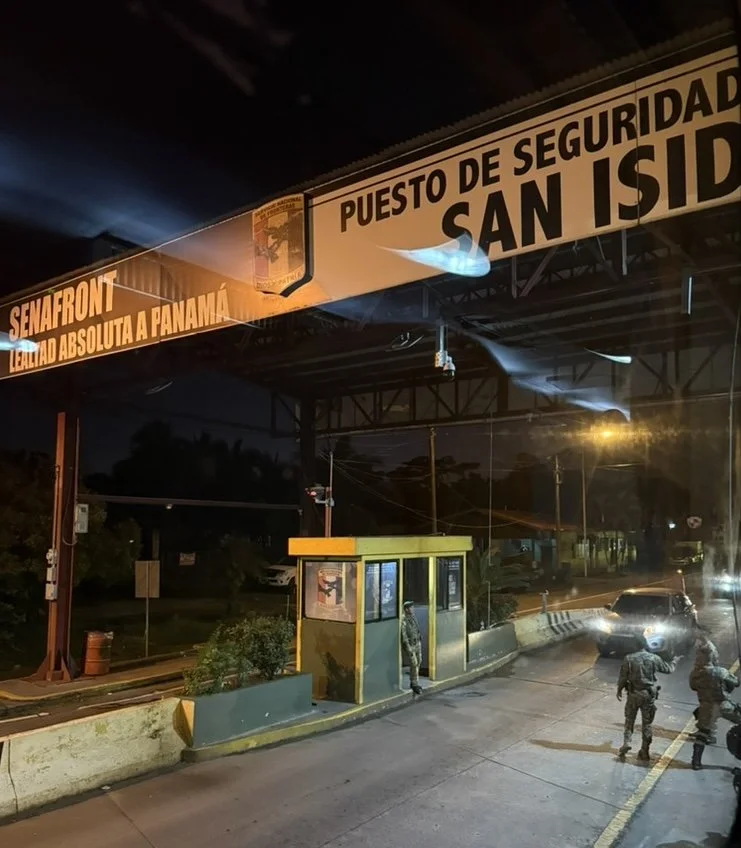

We arrived in Paso Canoas, Costa Rica, after 36 grueling hours of transit from Necoclí, Colombia. Our journey included a long car ride, two flights, and an eight-hour bus ride that felt like a mobile sauna. At 9 p.m., exhausted and relieved, we landed in Paso Canoas—on the Panamanian side of the border. We were greeted by a bustling town: taxis offering rides, buses lined up for transport, people trading currency on the streets, and the unmistakable airplane-hanglider structure emblazoned with “Panama.” Bags in hand and keenly aware of our vulnerability, we navigated quickly through the street vendors lining the sidewalk that connects Panama and Costa Rica.

How could we observe daily arrivals in Capurganá (from Panama), and yet see no signs of migrants further up the route in Paso Canoas? Reports had suggested that many people get “stuck” in Paso Canoas due to an inability to pay the hefty Panamanian travel package. And yet here we were, standing in the very place where people were supposedly stranded—and it felt empty of migrants.

This paradox became our working hypothesis: migrant flows through Paso Canoas have not disappeared but have gone underground—becoming decentralized, informal, and intentionally invisible. Over the coming days, our work would shift from seeking visibility to tracing invisibility—piecing together the shadow routes and informal strategies that shape today’s migration across the Costa Rica–Panama border.

Our first real lead came from a conversation with a long-distance bus driver en route to San José. He approached us, assuming we were catching the 9:30 a.m. departure. When we said no, we struck up a longer conversation. He casually mentioned that he had transported 15 migrants the night before and offered us his number. According to him, the two earliest buses—departing San José at 5:00 a.m. and 5:30 a.m.—carry the most migrants. These buses typically arrive in Paso Canoas around noon. While arrivals can occur throughout the day, he emphasized that midday is when “you’ll see them—if you’re looking.” We adjusted our observational strategy accordingly.

Later, we visited the Costa Rican migration office. We asked if anyone might be able to speak with us. Officials politely redirected us to an email and phone number for formal inquiries, reminding us they were not authorized to give interviews. That said, one moment stood out. A female officer quietly asked her male colleague, “Should we mention CATEM?” He quickly and sharply responded under his breath, “No.” The tone conveyed a sense of secrecy regarding the well-documented government run migrant holding and processing area. The male officer commented vaguely that migrants “can be found anywhere” and are largely “scattered and unpredictable.” When we asked for places to observe them, he shrugged: “They’re around the border.”

Despite pursuing various leads—staking out the bus terminal at midday, in the evenings, and again from 4:00 to 6:00 a.m.—we remained struck by the absence of visibility. It was not that migration had stopped, but that it had morphed, imperceptible. One key informant—a migrant himself—offered insights, “They’ll never tell you,” he said. “They know you don’t need the services—you’re gringos.”

It was a striking reminder: the invisibility of migration flows here is intentional, protective, and possibly strategic. In a border zone saturated by surveillance actors and law enforcement offices, the people have learned to move in ways that leave no trace. We’re taking the challenge head on and are hopeful the days to come will offer new insights.