Securitization without Security:

How Migration is Shaping the Global Order

notes from the field entry #4

SUNDAY MORNING TOUR WITH A LOCAL FRONTERIZA

Author: Greta Garcia Jalil Melendez

Location: El Paso, Texas

Date: July 13, 2025

From Tapachula we flew to Ciudad Juárez, an industrial city on Mexico’s northern border. We crossed the border by foot through the Paso Del Norte port of entry to get to El Paso, the home of my fieldwork partner, Dr. Gabriella Sanchez. As a local and a fronteriza – a person who lives at a border – she was the perfect person to host my first visit to the area.

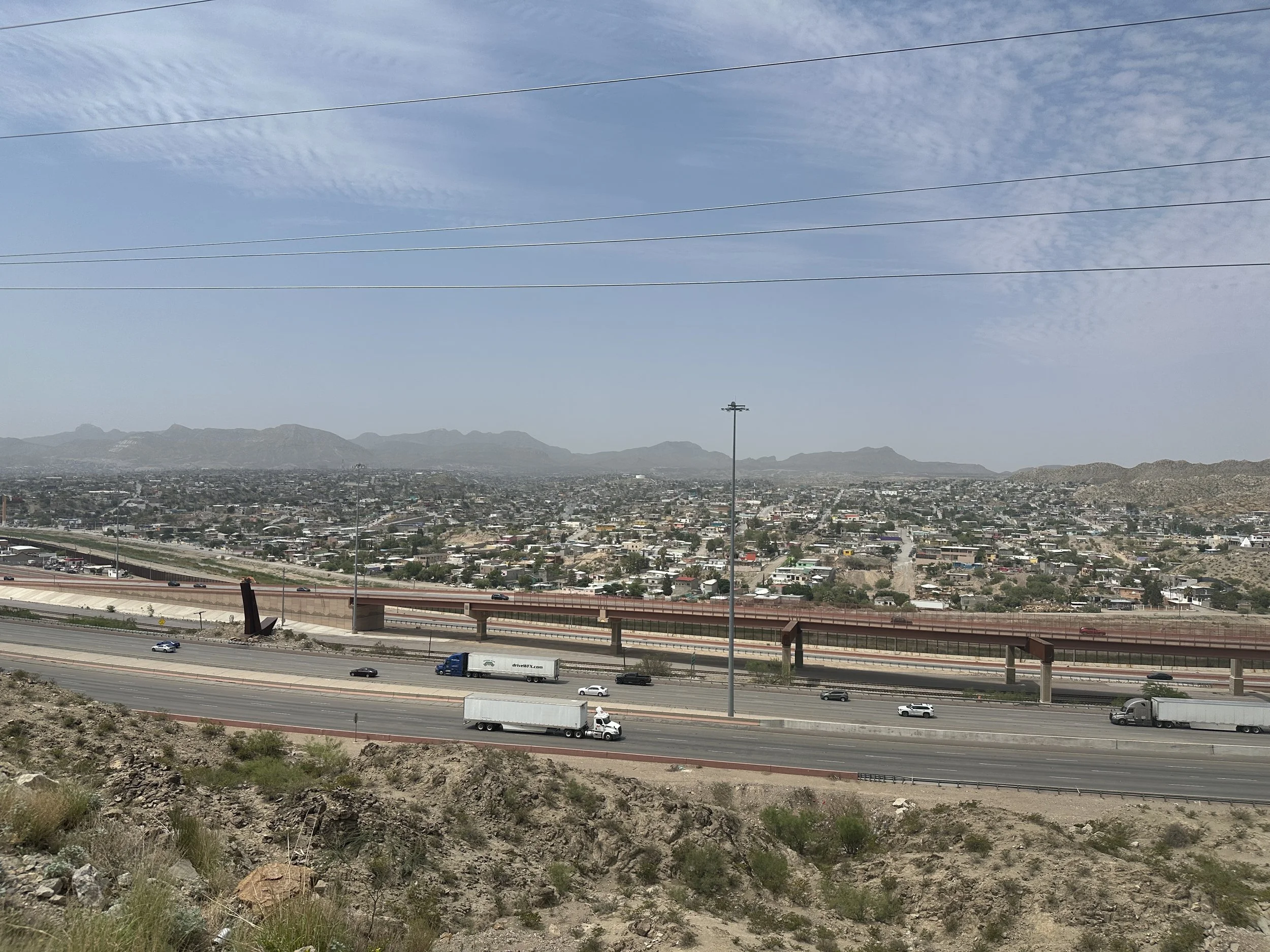

The next day, she took me to a lookout point near the University of Texas at El Paso, where I could see Ciudad Juárez. She told me about the maquiladora industry – manufacturing plants in Mexico that are owned by foreign companies. The maquiladora sector was created in 1965 after the conclusion of the Bracero program, a series of bilateral agreements from 1946 to 1964 that allowed Mexican farmworkers to work in the United States. The maquiladoras took off during the “lost decade” of the 1980s – a deep economic crisis that slashed Mexican wages and devalued its currency – and continued to grow after the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect in 1994. Employing mostly women, the maquilas paid higher wages than in the rest of Mexico but not enough to escape poverty. Dr. Sanchez pointed to a section of houses, known as colonias, where the factory workers reside because it is the most affordable option.

She then pointed out a white cross on top of a mountain, Mount Cristo Rey. At a distance it looks like a cross, but it is a statue of Jesus, which serves as a shrine. It is positioned at a unique point where Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico meet. Dr. Sanchez explained that parishioners visit this shrine, going on pilgrimage every year since the 1930s. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Las Cruces is currently embroiled in a conflict with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) over its plans to build a portion of the US. border wall south of Mount Cristo Rey, which would cut off access to the shrine for worshippers.

We continued driving to Sunland Park, New Mexico to look at a portion of the Río Grande, or the Río Bravo, unobstructed by the border. Although the river looked peaceful, Dr. Sanchez explained that it has an undercurrent, which puts migrants who try to swim across at risk of drowning. She explained the complex connection the local communities have with the river, mentioning an indigenous women’s group that hosts volunteers to plant native vegetation by the Río Grande as a restoration effort. Dr. Sanchez likes to sit by the river to read, but her favorite spot is now blocked by razor wire. I saw remnants of torn clothing stuck in the wire and wondered who had left it behind and what was their story. It is an image that will remain with me.

At another point along the border, a Border Patrol vehicle approached us before we could get close to the fence. Two men dressed in camouflage were in the vehicle. We did not see any signs, but the driver told us not to cross the train tracks because it is a “National Defense Area” (NDA). The vehicle followed us for about a mile after we turned the car around. El Paso’s NDA is the second of four, so far, that have been established by the U.S. Department of Defense along the U.S.-Mexico border. Although the military is prohibited from carrying out domestic law enforcement, it has jurisdiction over NDAs and so can legally detain migrants who enter before handing them over to the CBP or local law enforcement. It is yet another sign of the increasing militarization of Mexico’s borders.