Securitization without Security:

How Migration is Shaping the Global Order

notes from the field entry #2

Everyday Securitization at the Mexico-Guatemala Border

Author: Greta Garcia Jalil Melendez

Location: Tapachula, Mexico

Date: July 12, 2025

From personnel to checkpoints to billboards, the presence of security mechanisms was palpable in Tapachula, a city in the Mexican state of Chiapas just a few miles from the Guatemalan border. After landing at the Tapachula International Airport, we decided to explore the city and its outskirts. On the drive from the airport to Talismán, a border town across from El Carmen, Guatemala, we encountered multiple checkpoints. One checkpoint had state and federal police; another had tents, law enforcement, and the National Guard. We were permitted to pass without questions at every checkpoint. Other vehicles were stopped briefly, and trucks with products, such as platanos maduros [ripe bananas], were pulled over to be checked.

While we were at the Talismán-El Carmen border crossing, we met a Guatemalan man who had returned two years ago from the United States. He now works at a store in El Carmen and travels frequently to Mexico. He noted the increased presence of the Mexican military and law enforcement on the border and throughout Chiapas, which he attributes to irregular migration. We were a bit surprised when he expressed support for this increased presence, especially by the Pakales, which is shorthand for the Immediate Reaction Force Pakal (Fuerza de Reacción Inmediata Pakal). Established in December 2024 by the state government, the Pakales are an elite force focused on combating organized crime in Chiapas. In addition to operations, they patrol the highways and security checkpoints throughout the state, including Tapachula. Despite (or perhaps because of) his own migratory history, he believes that people should migrate regularly and criminals should be detained and deported. We later learned that he had been kidnapped and extorted on his journey north through Mexico.

As the days went by, I noticed the everyday presence of security mechanisms in populated areas of Tapachula. While we were walking around the San Juan Market, people cleared the way for a patrol vehicle. As it passed us, I noticed multiple personnel standing on the vehicle, armed with rifles, masked, and clad in black. I was taken aback, but the vendors and customers either glanced at them briefly or did not acknowledge them at all, suggesting that armed personnel in patrol vehicles are a common occurrence. When I returned to the hotel, I searched for the meaning of the acronym on the vehicle, “SSPPCM Tapachula.” Standing for Municipal Secretariat of Public Safety and Citizen Protection (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública y Protección Ciudadana Municipal), it is a law enforcement division of the municipal government of Tapachula. I added SSPPCM Tapachula to my running list of military and law enforcement divisions I had been noticing, such as border police (Policía Fronteriza), State Guard (Guardia Estatal), and National Guard (Guardia Nacional).

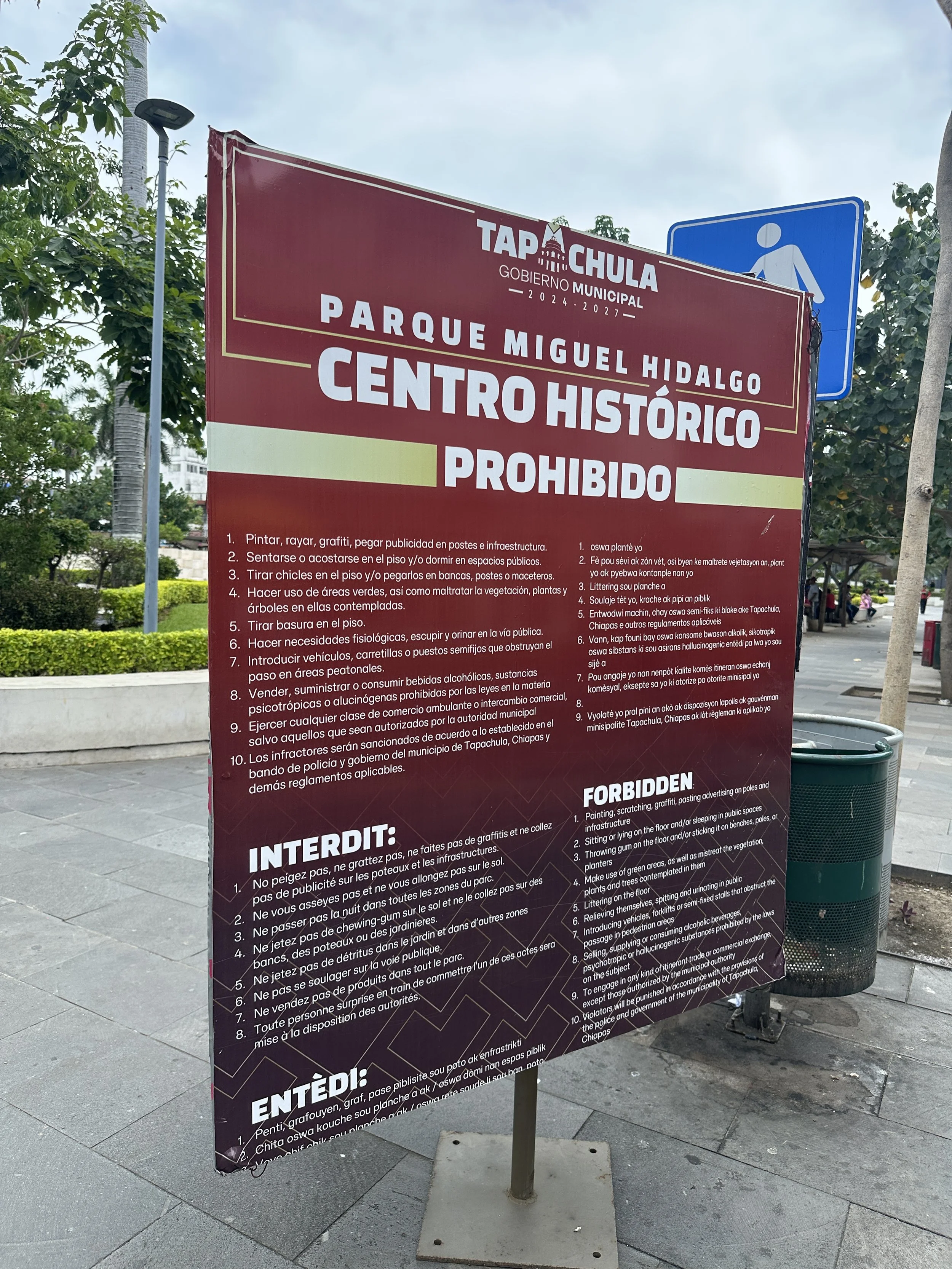

On a late Friday morning, I walked around Miguel Hidalgo Park in downtown Tapachula. At the entrance, there was a large sign placed by the local government, specifying what is prohibited in the park in multiple languages, including Spanish, English, and French. Given my previous observations and conversations, two prohibited items stood out to me:

- Prohibition 2: “Sitting or lying on the floor and/or sleeping in public spaces.”

- Prohibition 9: “To engage in any kind of itinerant trade or commercial exchange, except those authorized by the municipal authority.”

Upon further research, I learned that these rules were established to prevent people with luggage, mainly migrants, from using the park as a temporary residence.

As I walked by a few men polishing shoes and another doing temporary tattoos on a woman’s chest with black ink, I noticed municipal employees in blue vests with “Programa Centinela” on the back. I recalled an earlier interview with a key informant, who explained that these employees are tasked with monitoring individuals with backpacks. If an individual with a backpack sits or lays down for more than 15 minutes, the blue-vested monitor makes them either move or leave the park.

The narrative of securitization was everywhere we looked. Billboards installed by the state government touted slogans like “Zero Impunity” (Cero Impunidad), “Justice for the People” (Justicia para el pueblo), and “Chiapas Safe to Live” (Chiapas Seguro para Vivir). State law enforcement vehicles had the phrase “Zero Corruption” (Cero Corrupción) plastered on their windshields. Graffiti painted by the local government on the walls lining the streets announced “Safe Tapachula” (Tapachula Segura) and “100 Days Living in Peace” (100 días viviendo en paz). One of these billboards was located right outside the airport, making it among the first – and last – things I saw on my visit to the city.